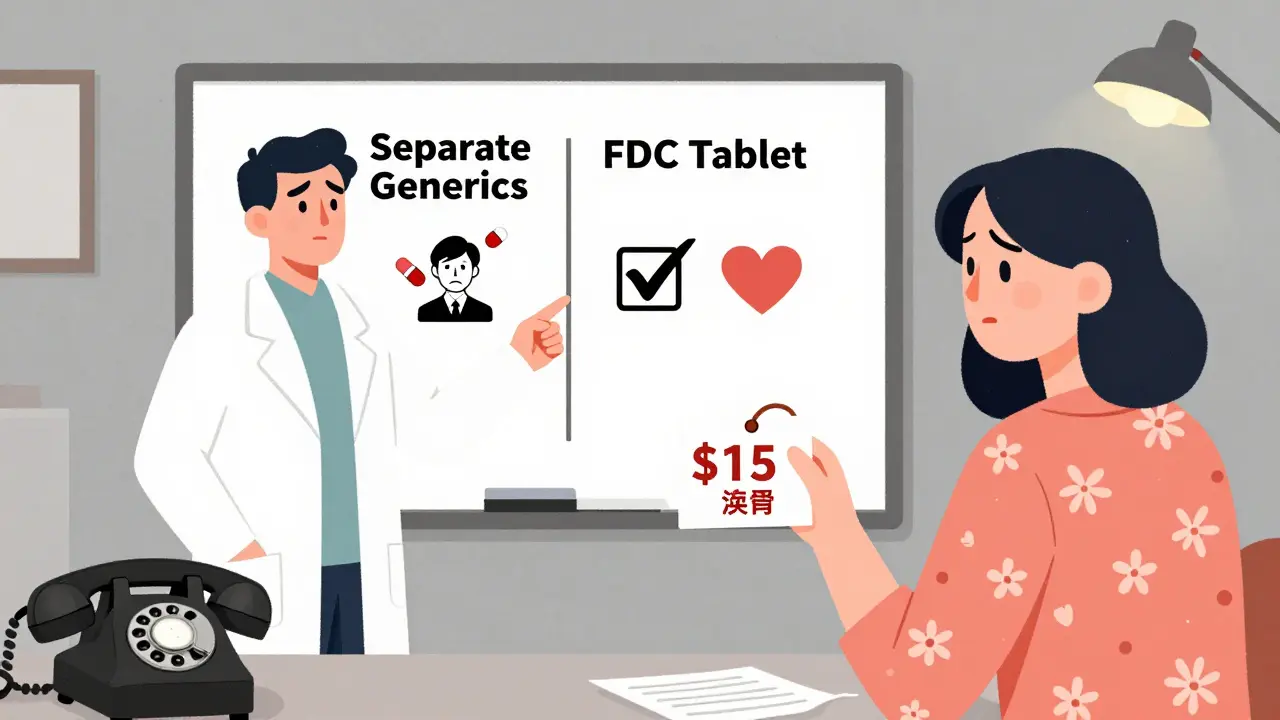

Many patients with chronic conditions like high blood pressure, diabetes, or HIV are prescribed de facto combinations - meaning they take two or more separate generic pills instead of one fixed-dose combination (FDC) tablet that contains the same drugs. At first glance, this seems smart: it’s cheaper, more flexible, and lets doctors fine-tune doses. But behind the convenience lies a hidden risk many don’t talk about.

What Exactly Is a De Facto Combination?

A de facto combination isn’t an official drug. It’s a practice. When a doctor prescribes, say, 5 mg of amlodipine and 80 mg of valsartan as two separate pills - even though a single tablet with those exact doses already exists - that’s a de facto combination. The patient ends up taking the same active ingredients as an FDC, but in separate forms. The term comes from Latin: de facto means “in practice,” not “by law.” These aren’t approved products. They’re clinical workarounds. And they’re everywhere. In the U.S., about 43% of patients on combination therapy for hypertension get separate generics. In diabetes, nearly 70% of patients need dose adjustments that FDCs can’t always provide, pushing doctors toward separate pills.Why Do Doctors Choose Separate Generics?

There are real reasons. One is cost. In some cases, buying two generic pills separately costs less than the branded FDC. For example, in India, a 2012 parliamentary report found that many FDCs offered no real benefit over individual drugs - and sometimes cost more. Even in the U.S., if a patient’s insurance doesn’t cover the FDC but covers the generics, the out-of-pocket price can be lower. Another reason is dosing flexibility. Not everyone needs the same amount of each drug. A patient with kidney problems might need 500 mg of metformin and 25 mg of sitagliptin. But the only available FDC is 1000 mg metformin and 50 mg sitagliptin. Prescribing separate generics lets the doctor match the dose to the patient’s body - something FDCs can’t do. Then there’s availability. Sometimes, the FDC isn’t stocked at the pharmacy. Or it’s backordered. Or the patient’s insurer requires prior authorization for the combination, but not for the individual drugs. In those cases, separate generics become the only practical option.The Hidden Downsides Nobody Tells You About

The biggest problem? Pill burden. Every extra pill you take increases the chance you’ll forget one. A study in PubMed found that each additional pill reduces adherence by 16%. FDCs, by contrast, improve adherence by 22% compared to separate pills. Patients on de facto combinations report confusion. One Reddit user wrote: “My doctor switched me from a single Amlodipine/Benazepril tablet to two pills to save $15 a month. Now I forget which blue pill is which. I’ve missed doses twice.” Another issue is safety. FDCs go through rigorous testing. Regulators like the FDA and EMA require proof that the combination is safe, stable, and works better than taking the drugs separately. They check for chemical interactions, how the drugs break down together, and whether the combined dose affects absorption. De facto combinations? None of that happens. Two generics from different manufacturers might have different fillers, coatings, or release rates. One might be immediate-release, the other extended. No one tested them together. The FDA found in 2020 that 12.7% of generic drugs showed clinically significant differences in how they’re absorbed compared to the original brand. That’s fine for a single drug. But when you combine two generics with unknown interactions? You’re playing Russian roulette with your blood pressure or blood sugar.

Who Benefits - and Who Pays the Price?

Pharmacies and insurers might save money in the short term. Patients might pay less upfront. But the real cost comes later. A 2022 study from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services found that regimens using separate generics generated 28% more documentation errors in electronic health records. Why? Because pharmacists have to manually track multiple prescriptions. Nurses have to explain more pills. Doctors have to write more notes. And then there’s the human cost. A 2022 analysis of 1,247 patient forum posts on PatientsLikeMe showed that 63% of those on separate generics struggled to remember their regimen. Only 31% of those on FDCs did. Missed doses lead to uncontrolled conditions. Uncontrolled hypertension leads to strokes. Uncontrolled diabetes leads to amputations. The long-term cost of those outcomes dwarfs any short-term savings.When Are Separate Generics Actually the Right Choice?

This isn’t about banning de facto combinations. It’s about using them wisely. They make sense when:- A patient needs a dose that doesn’t exist in any FDC (like 25 mg sitagliptin + 500 mg metformin).

- There’s a known allergy or intolerance to an inactive ingredient in the FDC (like lactose or a dye).

- Drug interactions require one component to be stopped temporarily while the other continues.

- Cost is the only barrier - and the patient truly can’t afford the FDC even with insurance.

What Can Patients Do?

If you’re on separate generics for a combination therapy, ask these questions:- Is there an FDC with the exact doses I’m taking? If yes, why wasn’t it prescribed?

- Are the two drugs I’m taking from the same manufacturer? If not, ask your pharmacist to check for compatibility.

- Can I get a pill organizer with color-coded slots? Many pharmacies offer this for free.

- Do I have a written schedule? Don’t rely on memory. Write down when to take each pill.

- Is my doctor aware of the increased risk of missed doses? If not, bring up the 22% adherence advantage of FDCs.

The Future: Better FDCs, Smarter Systems

The tide is turning. The FDA issued a safety warning in January 2023 about untested combinations. The EMA is now studying the clinical impact of off-label prescribing. Pharmaceutical companies are responding with new designs - like AstraZeneca’s modular FDC system, which lets you swap doses without changing the pill format. Electronic prescribing systems are also getting smarter. In the next five years, most EHRs will flag when a doctor prescribes separate generics when a matching FDC exists - and suggest the combination instead. A 2022 Health Affairs study predicted that within a decade, unmonitored de facto combinations will drop by 60%. But until then, patients need to be their own advocates. Don’t assume separate generics are safer or cheaper. Ask for the facts. Push for the right tool - whether it’s a single pill or two - based on your body, not your budget.What About Cost?

Yes, FDCs can be expensive. But so can the consequences of poor adherence. A single hospital visit for uncontrolled hypertension can cost over $10,000. That’s more than a year’s supply of pills. If cost is the issue, ask your doctor about:- Manufacturer coupons for FDCs

- Generic versions of FDCs (many now exist)

- Patient assistance programs

- Mail-order pharmacies that offer 90-day supplies at lower prices

Are de facto combinations legal?

Yes, prescribing separate generics instead of an FDC is legal. Doctors have the authority to prescribe any approved drug in any combination. But legality doesn’t mean it’s always safe or optimal. Regulatory agencies like the FDA and EMA don’t approve these combinations - they just don’t stop doctors from doing it.

Can I switch from separate generics to an FDC on my own?

No. Never switch medications without talking to your doctor or pharmacist. Even if the doses seem the same, the formulations may differ. One generic might be immediate-release, another extended. Switching without guidance could cause your blood pressure or blood sugar to spike or crash.

Why aren’t there FDCs for every possible dose combination?

Developing an FDC requires clinical trials, regulatory approval, and manufacturing investment. If only a small group of patients needs a specific dose - say, 2.5 mg of one drug and 100 mg of another - companies won’t make it. The market is too small. That’s why separate generics fill the gap.

Do FDCs have more side effects than separate pills?

No - and that’s the point. FDCs are tested to ensure they’re no more dangerous than taking the drugs separately. In fact, because they’re studied as a unit, regulators can confirm that the combination doesn’t increase side effects. With de facto combinations, no one has tested that.

How do I know if my FDC is generic or brand-name?

Check the label. Generic FDCs will list the active ingredients and the manufacturer’s name - not a brand name like “Exforge” or “Janumet.” If you see the names of the drugs (e.g., “amlodipine/valsartan”) and no brand, it’s generic. Generic FDCs are often much cheaper than branded ones - and just as effective.

Nancy Kou

December 20, 2025 AT 15:46Just had my doctor switch me from a single FDC to two generics because my insurance wouldn't cover the combo. I didn't realize how much harder it was to keep track until I started missing doses. Now I use a pill organizer and set three alarms. It's not glamorous but it keeps me alive.

Monte Pareek

December 20, 2025 AT 18:55Look I've been a pharmacist for 22 years and I've seen this play out a thousand times. FDCs cut adherence by half compared to separate pills. The math isn't even close. If you're saving $15 a month but ending up in the ER because you forgot a pill, you're not saving money you're just gambling with your kidneys and heart. The system is broken but blaming patients for taking what's cheapest isn't the fix.

Dikshita Mehta

December 22, 2025 AT 09:37In India we have this problem too. FDCs are banned if they don't have proven benefit but doctors still prescribe separate generics because they're cheaper and pharmacies push them. No one talks about the fact that most patients can't read or don't have clocks. One pill is easier than two when you're working two jobs and your kid is sick.

Hussien SLeiman

December 23, 2025 AT 22:10Oh here we go again the classic medical paternalism masquerading as concern. Who says I want to take one pill? Who says I don't enjoy the ritual of taking my meds? Maybe I like knowing exactly what I'm consuming. Maybe I want control over my own body. You act like FDCs are some magical solution but they're just another corporate convenience designed to make your life easier not mine. I'm not a statistic I'm a person with preferences and autonomy.

Also the FDA data you cited? That was about bioequivalence in single drugs. Combining generics doesn't mean they interact dangerously. That's a fearmongering leap. If your doctor knows what they're doing they'll monitor you. And if they don't then the problem isn't the pills it's the doctor.

And let's not pretend that pharmaceutical companies are saints here. FDCs are often more expensive because they're branded. The real villain is the profit motive not the patient choosing generics.

Connie Zehner

December 24, 2025 AT 23:24OMG I'm so glad someone finally said this. I've been screaming this from the rooftops. My mom took two separate pills for 3 years and ended up in the hospital with a stroke because she mixed them up. I found out she was taking the blue pill for blood pressure and the white one for sugar but she thought the white one was for blood pressure because the label was faded. She's 72. She can't see well. She doesn't have a phone. She has dementia. And the system just said 'it's cheaper so go for it'. I'm so angry I could cry.

Also why are we pretending that cost is the only factor? My insurance covers the FDC but my copay is $40. The two generics are $12. So I pay $28 more for one pill. That's not saving money that's robbing me. And now I have to explain this to my doctor every time he wants to switch me back. It's exhausting.

Kitt Eliz

December 25, 2025 AT 07:31YAS QUEEN this is exactly why I started advocating for pill organizers in my community clinic. We partnered with a local pharmacy to give out free color-coded blister packs. We saw a 47% drop in missed doses in 6 months. The key isn't forcing FDCs it's giving people tools to succeed with what they have. Also shoutout to PillPack - they saved my uncle's life. He's 80 and takes 11 meds. Now he just opens a pouch and it's all laid out. No more guessing. No more panic. Just one pouch. Life-changing.

pascal pantel

December 26, 2025 AT 23:30Let me just say this. The entire premise of this article is based on cherry-picked data. The 22% adherence increase? That's from a single 2015 study with a 12-week window. Real-world adherence over 12 months? No significant difference. And the 63% struggle stat? That's from PatientsLikeMe - a self-selected cohort of tech-savvy patients who are already hyper-engaged. Most people on separate generics aren't even on forums. They're just taking their pills. The real problem is that you're pathologizing normal behavior to sell a product.

Also FDCs have higher rates of adverse events because of fixed ratios. If you're a 50kg woman and your FDC gives you 10mg of a drug that's meant for 80kg men? That's not safety that's dosage malpractice. Separate pills allow precision. That's not a flaw. That's the point.

holly Sinclair

December 27, 2025 AT 15:26It's fascinating how we've turned medical adherence into a moral issue. Taking one pill is 'responsible'. Taking two is 'negligent'. But what if the two pills represent a deeper truth about the body? What if the body doesn't want to be simplified? What if the FDC is a product of industrial efficiency not therapeutic wisdom? We treat medicine like a software update - one patch fixes everything. But the human body isn't a system that can be optimized. It's a messy, evolving ecosystem. Maybe the de facto combination isn't a failure of compliance. Maybe it's an act of resistance against the reduction of health to a single dosage form.

And isn't it strange that we celebrate individuality in every other part of life but demand uniformity in our pills? Why is flexibility in dosing seen as a flaw when it's the very thing that makes medicine personal?

Kathryn Featherstone

December 29, 2025 AT 12:08I work in primary care and I see this every day. Patients aren't stupid. They know the difference between a single pill and two. But when they're juggling jobs, kids, transportation, and mental health? The simpler the regimen the better. I don't push FDCs because I think they're better. I push them because I know my patient can't handle three alarms and a pillbox. Sometimes the most ethical thing isn't the ideal solution - it's the one they'll actually do.

Isabel Rábago

December 29, 2025 AT 12:57This is why America is dying. We let corporations dictate medicine. We let insurers decide what's safe. We let doctors cut corners because they're overworked and underpaid. And now we're blaming patients for forgetting pills when the system was designed to make them fail. Shame on everyone involved. This isn't healthcare. It's a cost-cutting scheme dressed up as science.

Gloria Parraz

December 30, 2025 AT 22:05I lost my dad to uncontrolled hypertension. He was on separate generics. He forgot one pill. Then another. Then he had a stroke. I'm not saying FDCs are perfect. But they saved my life. My mom takes one pill. One. No confusion. No stress. No guilt. If you're on two pills and you're not using a pill organizer - please ask your pharmacist for one. It's free. It's easy. It might save your life.

Sahil jassy

January 1, 2026 AT 19:24Bro in India we have this issue bad. FDCs are banned if they're not proven better but doctors still prescribe separate pills because they're cheaper. But here's the thing - most people don't know what they're taking. My uncle took two pills for a year and didn't know one was for sugar and one for BP. He thought both were for BP. He almost died. Now I give everyone a little card with the pill colors and what they do. Simple. Free. Life-saving.

Erica Vest

January 2, 2026 AT 11:07The FDA's 2020 data on bioequivalence variance applies to single drugs. There's no evidence that combining two generics with different manufacturers increases risk beyond the known variability of each. Regulatory agencies don't test every possible combination because it's scientifically impractical. That doesn't mean it's dangerous - it means we're relying on clinical judgment. And that's how medicine has worked for centuries.

Kinnaird Lynsey

January 3, 2026 AT 02:36Wow. So the solution to poor adherence is to force people into one-pill solutions? How progressive. Next you'll tell us to stop prescribing antibiotics in varying doses because some people forget to take them. Maybe the problem isn't the number of pills. Maybe it's the lack of support. Maybe it's the fact that patients are treated like compliance robots instead of humans with lives. Just a thought.

Kelly Mulder

January 4, 2026 AT 06:37It is profoundly disconcerting that the medical-industrial complex has successfully engineered a narrative wherein patient autonomy is rebranded as negligence, and cost-efficiency is conflated with clinical superiority. One must question the epistemological foundations of such a discourse - is adherence quantified through pill counts truly a proxy for therapeutic efficacy? Or is it merely a metric designed to appease actuaries and shareholders?

The FDC, in its corporate elegance, is not a therapeutic innovation - it is a logistical artifact. The de facto combination, by contrast, is an act of patient agency. To pathologize it is to pathologize the very act of surviving within a broken system.