Idiosyncratic Reaction Symptom Checker

What This Tool Does

Idiosyncratic drug reactions are rare, unpredictable side effects that often appear 1-8 weeks after starting a medication. This tool helps you determine if your symptoms might indicate an idiosyncratic reaction (Type B), which requires immediate medical attention.

Check Your Symptoms

Enter information about your medication and symptoms below to see if you might be experiencing a rare drug reaction.

Enter information above to see results

Most people expect side effects from medications-maybe a headache, upset stomach, or drowsiness. But what if your body reacts in a way no one saw coming? No one predicted it. No test could catch it. That’s an idiosyncratic drug reaction-a rare, unpredictable, and sometimes life-threatening response that strikes only a handful of people, often after weeks of taking a drug safely.

What Makes a Drug Reaction ‘Idiosyncratic’?

Not all side effects are the same. About 80-85% of adverse reactions are predictable. These are called Type A reactions. They happen because the drug does what it’s supposed to do-just too much. Take too much acetaminophen? Liver damage. Too much blood pressure medicine? Dizziness. These are dose-dependent. You can see them coming.

Idiosyncratic drug reactions (IDRs), or Type B reactions, are different. They don’t follow the rules. You could take the exact same dose as someone else and be fine. But for a few unlucky people, something inside their body flips a switch. Their immune system starts attacking. It’s not about the dose. It’s about who you are.

These reactions are rare-about 1 in 10,000 to 1 in 100,000 patients. But they’re dangerous. They cause 30-40% of all drug withdrawals from the market. Drugs like troglitazone (for diabetes) and bromfenac (a painkiller) were pulled because of these unpredictable reactions. Even though they worked well for most, the risk for a few was too high.

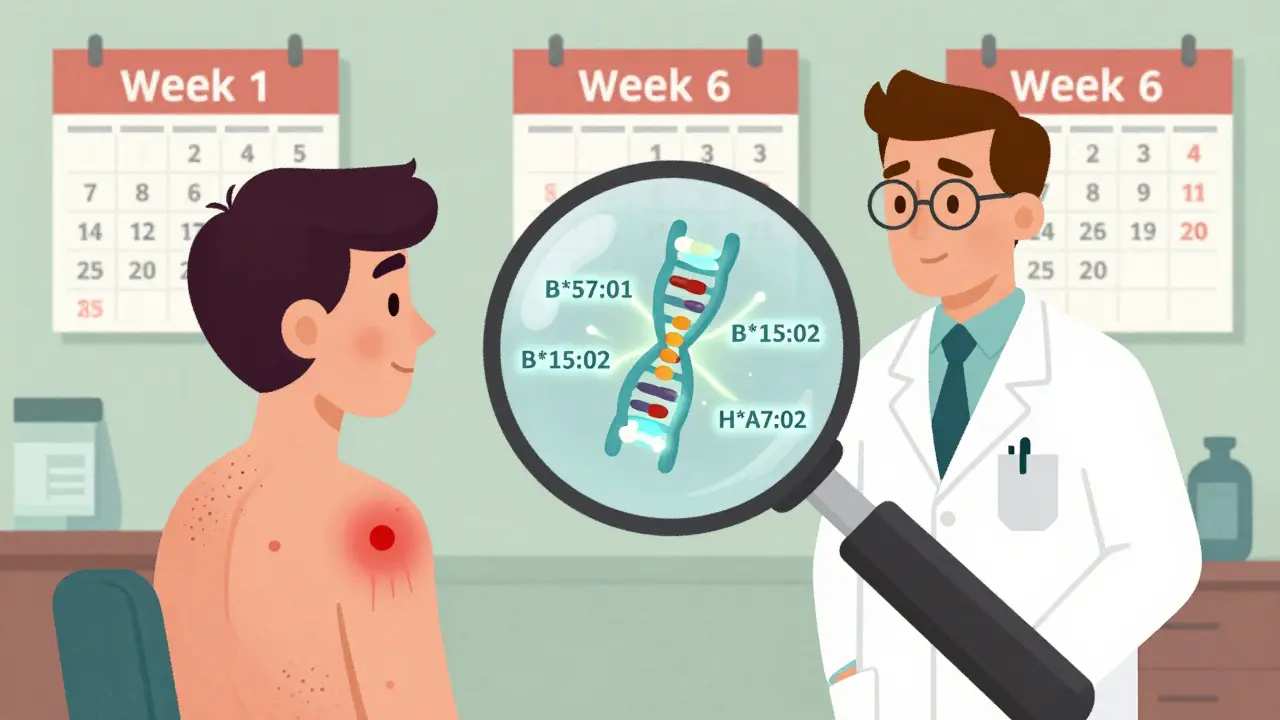

When Do These Reactions Happen?

IDRs don’t show up right away. That’s one of the biggest traps. You start a new medication. You feel fine for days, even weeks. Then, out of nowhere, symptoms appear. Most reactions kick in between 1 and 8 weeks after you begin taking the drug.

This delay is why so many people are misdiagnosed. A rash, fever, and fatigue? Doctors think it’s the flu. Liver enzymes spiking? Maybe it’s hepatitis. It’s not until the drug is stopped-and symptoms improve-that the real cause becomes clear. This is called a “dechallenge.” If symptoms return when the drug is restarted (a “rechallenge”), it’s almost certain the drug caused it. But doctors rarely rechallenge because it’s risky.

Most Common Types of Idiosyncratic Reactions

Two types dominate the clinical picture:

- Idiosyncratic drug-induced liver injury (IDILI): This is the most common, making up nearly half of all severe drug-related liver damage. It can look like hepatitis-fatigue, nausea, yellow skin, dark urine. Some cases are mild and go away. Others lead to liver failure. About 5-10% of severe IDILI cases are fatal.

- Severe cutaneous adverse reactions (SCARs): These are skin and immune system disasters. They include Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS), toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN), and DRESS syndrome (Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms). TEN is especially deadly-up to 35% of patients don’t survive. These reactions often start with a red, painful rash that blisters and peels off like a burn.

Other reactions can affect the lungs, kidneys, or blood cells, but liver and skin issues are the most frequent and most studied.

Why Do Only Some People Get Them?

This is the million-dollar question. Scientists have spent decades trying to figure it out. The leading theory is the hapten hypothesis. It says some drugs break down in the body into reactive chemicals. These chemicals stick to your own proteins, turning them into something the immune system doesn’t recognize. Your body sees them as invaders and attacks.

But why you and not your neighbor? Genetics play a huge role. Certain gene versions make you more vulnerable. The most famous example is HLA-B*57:01. If you have this gene and take the HIV drug abacavir, your risk of a life-threatening allergic reaction jumps dramatically. Testing for this gene before prescribing abacavir is now standard-and it’s cut reactions to nearly zero.

Another example is HLA-B*15:02. People with this gene, especially in Southeast Asia, are at high risk for SJS/TEN when taking carbamazepine (for seizures or bipolar disorder). Testing for this gene before prescribing is now required in many countries.

But here’s the problem: only two drugs have reliable genetic tests. For the rest-over 90% of IDRs-there’s no way to predict who’s at risk. That’s why these reactions remain so terrifying.

How Do Doctors Diagnose Them?

There’s no single blood test or scan that confirms an IDR. Diagnosis is a puzzle. Doctors use tools like:

- RUCAM: A scoring system for liver injury. A score above 8 means the drug is “highly probable” as the cause.

- ALDEN: A tool for skin reactions like SJS/TEN. It looks at timing, symptoms, and drug history.

They also look at:

- Timing: Did symptoms start 1-8 weeks after starting the drug?

- Severity: Is the reaction way worse than expected?

- Exclusion: Could something else be causing it? Infection? Autoimmune disease?

Even then, it’s not perfect. Studies show that 35% of liver injury cases are misdiagnosed at first. Many patients are sent home with a “viral illness” diagnosis-only to return weeks later in critical condition.

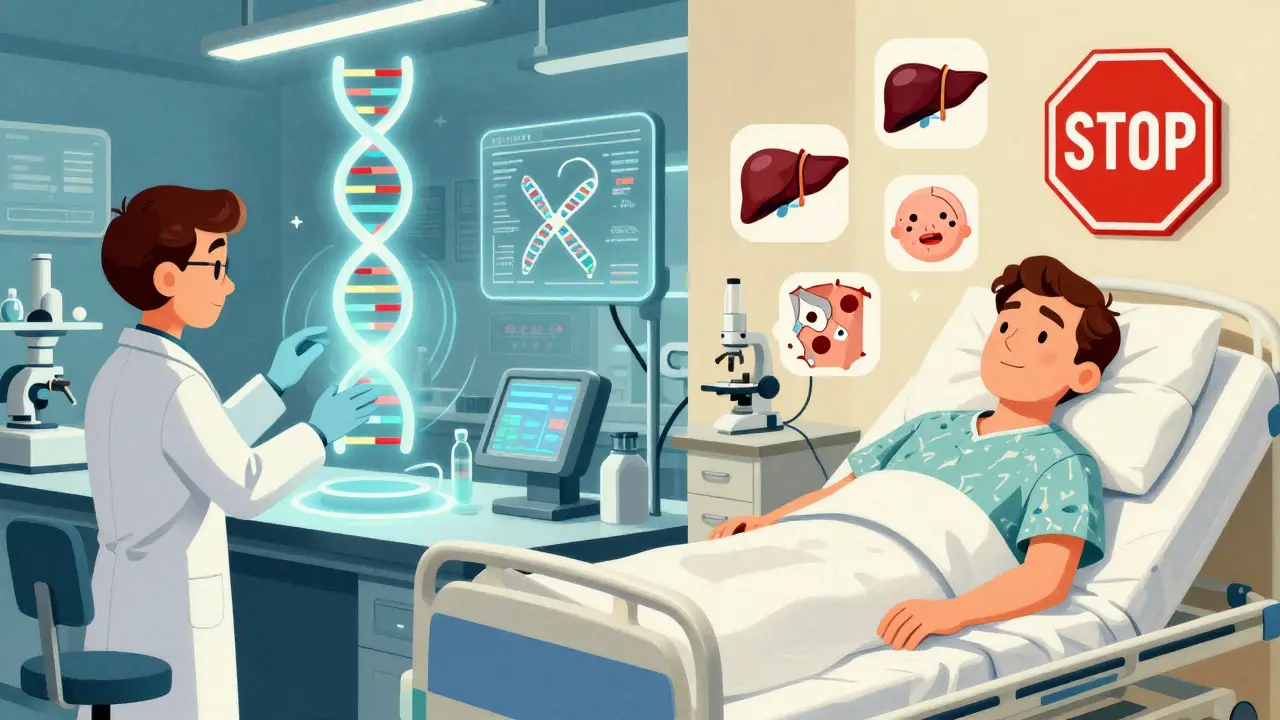

What Happens After Diagnosis?

Step one: Stop the drug. Immediately. No exceptions.

Step two: Supportive care. For liver injury, that means monitoring liver enzymes, fluids, and sometimes a liver transplant. For skin reactions, patients often need intensive care-like burn units. Steroids and immunosuppressants are sometimes used, but their effectiveness is debated.

Step three: Long-term follow-up. Some people recover fully. Others are left with chronic liver damage, nerve problems, or skin scarring. The DRESS Syndrome Foundation found that 28% of patients needed ongoing specialist care after recovery.

And emotionally? Many patients say they felt dismissed. One person described being told, “It’s probably just allergies,” while their skin was peeling off. The average delay in diagnosis is over 17 days. That’s 17 days of suffering without the right treatment.

Why Is This Such a Big Problem for Drug Companies?

IDRs cost the pharmaceutical industry billions. The Tufts Center estimates $12.4 billion a year in lost drugs, failed trials, and post-market withdrawals. Companies spend millions screening for reactive metabolites-chemicals that might trigger these reactions. In 2005, only 35% of drugmakers did this. By 2023, it was 92%.

Regulators like the FDA now require detailed metabolite testing for any drug that breaks down into more than 10% of its original form in the body. New guidelines, like the 2023 ICH M17, force companies to think about immune reactions from day one of drug design.

But even with all this, prediction is still limited. AI tools are being built to spot patterns in genetic and chemical data, but none have cracked the code yet. The best tools today are only 70-80% accurate.

What’s Changing in 2026?

There’s real progress. In 2023, the FDA approved the first predictive test for pazopanib-a cancer drug that can cause liver damage. The test uses genetic and protein markers to identify high-risk patients with 82% accuracy. That’s a game-changer.

Researchers have also found 17 new gene-drug links since 2022, including one for phenytoin and SJS/TEN. The NIH has poured $47.5 million into the Drug-Induced Injury Network to study the biological mechanisms behind these reactions.

By 2027, the European Commission’s ADRomics project aims to combine DNA, protein, and immune data to predict reactions before a drug even hits the market. If it works, it could cut severe IDRs by 60-70% in the next decade.

But experts warn: we’ll never eliminate them entirely. The human immune system is too complex. The goal isn’t perfection-it’s prevention. Knowing who’s at risk, catching reactions early, and stopping drugs before it’s too late.

What Should You Do?

If you’re starting a new medication:

- Know the signs: Unexplained fever, rash, yellow eyes, dark urine, severe fatigue.

- Track timing: Did symptoms start 1-8 weeks after starting the drug?

- Speak up: If something feels wrong, don’t wait. Say, “Could this be a reaction to my new medicine?”

- Ask about testing: If you’re prescribed abacavir, carbamazepine, or other high-risk drugs, ask if genetic screening is available.

- Keep a list: Write down every drug you take, including doses and start dates. Bring it to every appointment.

If you’ve had a reaction before: Never take that drug again. Tell every doctor. Even over-the-counter meds can trigger cross-reactions.

IDRs are rare. But when they happen, they change lives. The more we understand them, the better we can protect people. And that’s the point.

What’s the difference between a common side effect and an idiosyncratic reaction?

Common side effects (Type A) happen to many people and are related to the drug’s known action-like nausea from antibiotics or drowsiness from antihistamines. They usually appear right away and get worse with higher doses. Idiosyncratic reactions (Type B) are rare, unpredictable, and not dose-related. They often appear weeks after starting the drug and can be life-threatening, like liver failure or severe skin reactions. They’re caused by individual biology, not the drug’s main effect.

Can I be tested for idiosyncratic drug reactions before taking a medication?

Only for a few drugs. The most common tests are for HLA-B*57:01 before taking abacavir (an HIV drug) and HLA-B*15:02 before taking carbamazepine (for seizures or bipolar disorder). These tests are highly accurate and now standard in many countries. For almost all other drugs, no reliable pre-testing exists. Researchers are working on broader genetic and immune panels, but nothing is widely available yet.

How long does it take for an idiosyncratic reaction to show up?

Most idiosyncratic reactions appear between 1 and 8 weeks after starting the drug. This delay is why they’re so hard to spot. Many patients are misdiagnosed during this time, often told they have the flu, a viral infection, or a skin allergy. The longer the delay, the harder it is to connect the reaction to the drug.

Are idiosyncratic reactions more dangerous than common side effects?

Yes, in terms of severity. While common side effects are usually mild and temporary, idiosyncratic reactions can be fatal. Severe drug-induced liver injury has a 5-10% death rate. Toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) kills 25-35% of patients. These reactions often require hospitalization, intensive care, or even organ transplants. They’re rare, but when they happen, they’re serious.

Can you get an idiosyncratic reaction from a drug you’ve taken before?

Yes. Unlike allergic reactions, which usually happen after prior exposure, idiosyncratic reactions can occur the first time you take a drug-or the tenth. There’s no rule. Some people take a drug for years without issue, then suddenly develop a reaction. That’s why doctors warn against assuming safety based on past use.

What should I do if I suspect I’m having an idiosyncratic reaction?

Stop taking the drug immediately and contact your doctor. Don’t wait. If you have symptoms like a rash that spreads, blisters, yellow skin, dark urine, fever, or severe fatigue, go to an emergency room. Bring your medication list. Say clearly: “I think this might be an idiosyncratic reaction.” Early recognition saves lives. Many patients are misdiagnosed for days or weeks-don’t let that happen to you.