When your heart beats, it follows a precise electrical rhythm. That rhythm shows up on an ECG as a series of waves - P, Q, R, S, and T. The time between the start of the Q wave and the end of the T wave is called the QT interval. If this interval gets too long, it’s called QT prolongation. And that’s not just a number on a graph. It can mean the difference between a safe day and a life-threatening arrhythmia called torsades de pointes - a chaotic, fast heartbeat that can turn into cardiac arrest.

QT prolongation doesn’t always happen on its own. In fact, the most common cause today isn’t genetics. It’s medications. Over 200 drugs - from antibiotics to antidepressants to heart pills - are known to stretch this interval. Some do it mildly. Others can push it into the danger zone. And when that happens, especially with other risk factors, the chance of sudden death goes up sharply.

How QT Prolongation Turns Deadly

The heart’s electrical system relies on ions - potassium, sodium, calcium - moving in and out of heart cells in a timed sequence. The QT interval measures how long it takes the ventricles to recharge after each beat. When certain drugs block a specific potassium channel called hERG (encoded by the KCNH2 gene), the recharge phase slows down. That’s the core problem. A longer recharge means the heart muscle stays electrically unstable longer, creating a perfect setup for a dangerous feedback loop: one early beat triggers another, then another - spiraling into torsades de pointes.

The risk isn’t the same for everyone. Women are at higher risk - about 70% of documented torsades cases occur in women. Older adults, people with low potassium or magnesium, those with heart disease, and those taking multiple QT-prolonging drugs are also more vulnerable. A QTc (corrected QT interval) over 500 milliseconds is a red flag. But even a jump of more than 60 milliseconds from baseline can be dangerous, especially if you’re on a high-risk drug.

Drugs That Carry the Highest Risk

Not all QT-prolonging drugs are created equal. Some are designed to slow the heart’s rhythm - like antiarrhythmics - but even those can backfire. Others are everyday meds people never expect to be risky.

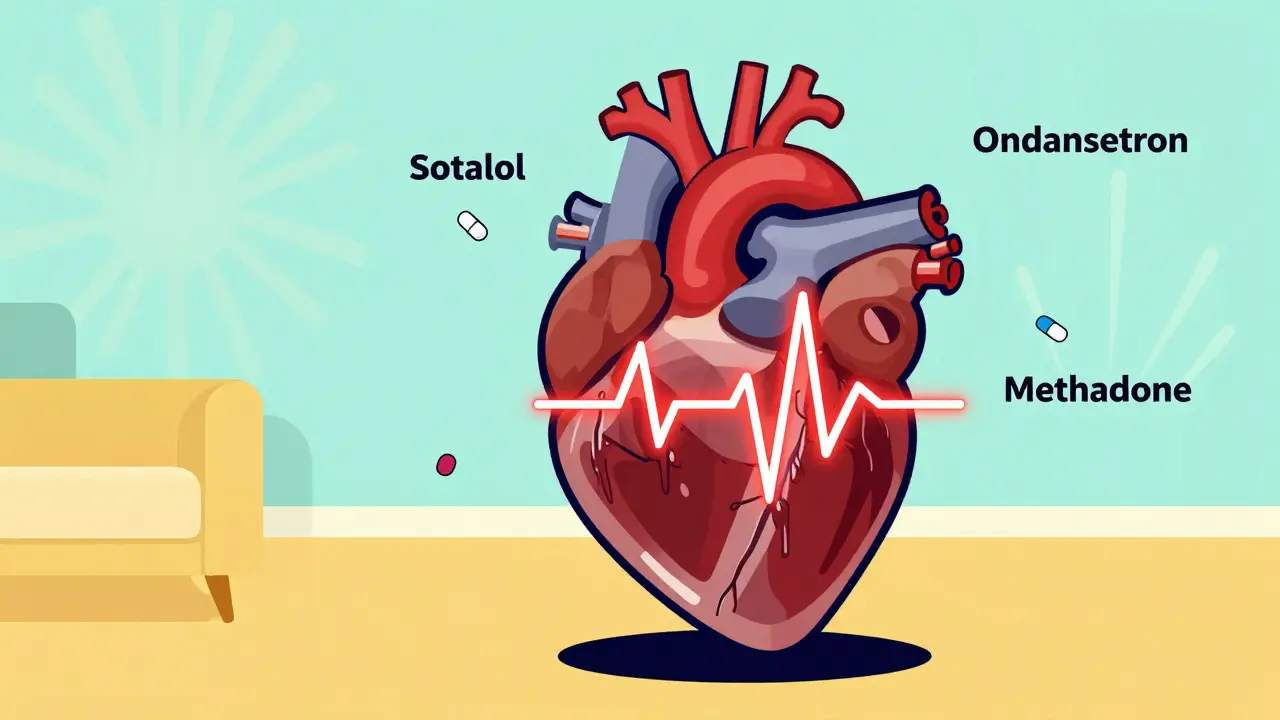

- Class III antiarrhythmics: Sotalol and dofetilide are made to prolong repolarization. But they come with a trade-off: sotalol causes torsades in 2-5% of patients, while dofetilide carries a 5-8% risk in clinical trials. Amiodarone also prolongs QT, but its multi-channel effects make torsades less common - around 0.7-3%.

- Class Ia antiarrhythmics: Quinidine and procainamide are older drugs, but they’re still used. Quinidine has been linked to torsades in up to 6% of patients - one of the highest risks of any medication.

- Antibiotics: Erythromycin and clarithromycin can prolong QT by 15-25 ms, especially when taken with drugs that block their metabolism (like grapefruit juice or antifungals). Moxifloxacin is another common offender, adding 6-10 ms on average.

- Antipsychotics: Ziprasidone and haloperidol carry black box warnings from the FDA for arrhythmia risk. Ziprasidone’s label specifically warns of ventricular arrhythmias. In real-world cases, haloperidol is often involved in overdose or rapid IV use.

- Antiemetics: Ondansetron (Zofran) is given to millions for nausea - but it’s one of the top drugs linked to torsades in FDA reports. A 2020 review found it involved in 42% of reported TdP cases.

- Antidepressants: Citalopram and escitalopram are known for dose-dependent QT prolongation. The FDA limited citalopram to 40 mg/day (20 mg for patients over 60) because of this.

- Opioid maintenance: Methadone is a major concern. Doses above 100 mg/day significantly raise QTc. Many patients on methadone maintenance have QTc values over 470 ms - but with proper monitoring, TdP can be avoided.

When Risk Multiplies: The Power of Combinations

One risky drug? Maybe manageable. Two or three? That’s where things get dangerous.

A 2017 study showed that combining QT-prolonging drugs doesn’t just add risk - it multiplies it. For example, giving haloperidol and ondansetron together can push QTc up by 40-60 ms - enough to cross into the danger zone. A Reddit thread from a 2022 emergency physician described a 65-year-old woman who got standard doses of ondansetron and azithromycin for stomach flu. Her QTc jumped from 440 ms to 530 ms in 24 hours. She needed ICU care.

Drug interactions make this worse. Many QT-prolonging drugs are metabolized by the liver enzyme CYP3A4. If another drug - like a fungal infection treatment (fluconazole) or even grapefruit juice - blocks that enzyme, the QT-prolonging drug builds up in the blood. That’s why a normal dose can become toxic.

Who’s at Greatest Risk?

It’s not just the drug. It’s the person taking it.

- Women: Estrogen affects ion channels. Postmenopausal women and those in the postpartum period are especially vulnerable.

- Older adults: Kidney and liver function decline with age. Drugs stick around longer. Over 65s are 3-4 times more likely to develop TdP.

- Low electrolytes: Potassium below 4.0 mmol/L or magnesium below 1.8 mg/dL dramatically increases risk.

- Heart disease: Structural problems like heart failure or prior heart attack make the heart more sensitive to electrical instability.

- Genetics: About 30% of drug-induced torsades cases involve a hidden genetic variant in the hERG channel. You might not know you have it until you take a risky drug.

What Should You Do? Practical Steps

Most people won’t need an ECG before taking a pill. But if you’re on one of these high-risk drugs - or multiple ones - you need a plan.

- Ask your doctor: If you’re prescribed a new medication, ask: “Does this affect the QT interval?” If you’re on methadone, sotalol, or ondansetron, this is non-negotiable.

- Get a baseline ECG: Especially if you’re over 65, female, or have heart disease. The European Society of Cardiology recommends this before starting high-risk drugs.

- Check electrolytes: A simple blood test for potassium and magnesium is cheap and can prevent disaster.

- Review all meds: Include OTC drugs, supplements, and herbal products. Even some cough syrups and antacids can interact.

- Monitor after starting: Repeat the ECG within 3-7 days after starting or increasing the dose of a high-risk drug.

- Know the warning signs: Dizziness, fainting, palpitations, or unexplained seizures could be early signs of torsades. Don’t wait.

What’s Changing in Drug Safety

The way drugs are tested for QT risk is evolving. The old method - just measuring QT interval - wasn’t enough. Now, the Comprehensive in vitro Proarrhythmia Assay (CiPA) uses computer models and tests drugs on multiple ion channels. Since 2016, this has led to 22 drug failures in development - meaning safer drugs are getting approved.

AI is also stepping in. A 2024 study showed an algorithm could predict torsades risk with 89% accuracy by analyzing tiny details in ECG waveforms - not just the QT number. That could mean future ECGs give not just a number, but a risk score.

And the list of risky drugs keeps growing. In November 2023, the obesity drug retatrutide was added to the risk list after showing 8.2 ms of QT prolongation in trials. The FDA will require full CiPA testing for all new drugs starting in January 2025.

Bottom Line

QT prolongation is silent. It doesn’t hurt. It doesn’t cause symptoms until it’s too late. But it’s preventable. The key is awareness. If you’re taking any of these medications - especially in combination - don’t assume it’s safe. Talk to your doctor. Get your ECG. Check your levels. Ask about alternatives. Most cases of torsades happen because someone didn’t connect the dots. You can avoid that.

Can a single medication cause torsades de pointes?

Yes, but it’s rare with most drugs at normal doses. High-risk medications like dofetilide, quinidine, or sotalol can cause torsades even alone. For drugs like ondansetron or citalopram, torsades usually happens when combined with other risk factors - like low potassium, an existing heart condition, or another QT-prolonging drug.

Is QT prolongation always dangerous?

No. Mild prolongation (QTc 450-499 ms) is common and often harmless, especially in athletes or people with slow heart rates. Danger starts when QTc exceeds 500 ms, or if it increases by more than 60 ms from baseline. That’s when the risk of torsades rises sharply.

Do all antibiotics prolong the QT interval?

No. Only certain ones do - primarily macrolides like erythromycin and clarithromycin, and fluoroquinolones like moxifloxacin. Penicillins, cephalosporins, and tetracyclines generally do not affect QT. Always check the drug’s safety profile.

Can I still take my antidepressant if it prolongs QT?

Yes - but with caution. For many patients, the benefits of treating depression outweigh the small risk of torsades. However, if you’re over 65, have heart disease, or are on other QT-prolonging drugs, your doctor may switch you to a safer option like sertraline or citalopram (at the lowest dose). Never stop your medication without medical advice.

How often should I get an ECG if I’m on a QT-prolonging drug?

Baseline ECG before starting is essential. Then, repeat within 3-7 days after beginning or increasing the dose. If your QTc stays stable and you have no other risk factors, further monitoring may not be needed. But if your QTc rises above 500 ms or you develop symptoms, stop the drug and seek help immediately.

Mike Hammer

February 14, 2026 AT 22:27Been on methadone for 5 years. QTc was 480 at baseline. Doc ordered ECG every 3 months, potassium checks, and banned grapefruit juice. No issues. It's not about fear - it's about awareness. Simple stuff works if you actually do it.